Electricity is a commodity and in the last 25 years, in most countries of the world, it has evolved from being a nationalized commodity (inaccessible for the private sector) to becoming a regulated market. Regulation has allowed the private sector to participate more or less freely in some of its services. The commercialization of electric energy for final consumers, for example, is now a liberalized service accessible to any company and in which the final customer (above a minimum consumption) can decide which company to pay their electricity bill to. Electricity generation, for example, unlike commercialization, is still heavily regulated given the high capital costs and strategic importance of this service for countries. And if the rules of regulated electricity markets are met, only energy trading companies could monetize an electric vehicle charging station, creating a quasi-monopoly in the hands of the electricity traders for an asset of which we need to deploy hundreds of thousands of units in a record time. The United States, for example, has fewer than 125,000 gasoline stations nationwide but will require more than 1 million charging points in public space in less than 10 years.

The fact is that the leading countries in adopting electric mobility (EM), (all of Europe, Chile in Latin America, and most of the United States) have been quick to exclude from the regulated market the sale of electric car station power. This has allowed any company to monetize charging processes. Whether as a service or as an electric power sale, it is legal to monetize an EV charging station in these countries. In other ones, Spain for example, even excluding EM from the regulated market, companies interested in monetizing were required to fulfill additional processes. The number of candidates that showed interest was totally insufficient for the deployment of charging stations that were required, and finally, all restrictions were eliminated.

There are other territories for which electricity is a national good (not regulated but exclusively owned by the State) and therefore no interference from the private sector is allowed (or if allowed, it is the State that sets the prices in its commercialization) such as Uruguay and Costa Rica. Here, the entire effort for the adoption of EM is on the government. And the private sector will not have enough financial incentive to help the deployment.

Finally, in the USA, in those states where EM has not been explicitly excluded from the regulated market, EM is monetized but only as a “SERVICE”, not as a sale of electricity. In other words, it is not allowed to bill by kWh but by the hour.

In those places where the private sector has led the deployment of charging stations, the question arises as to which is the most appropriate way to generate revenue, by energy delivered (kWh), by charging time or by a mixed-formula, and also whether it is the State that has to decide which one of the three.

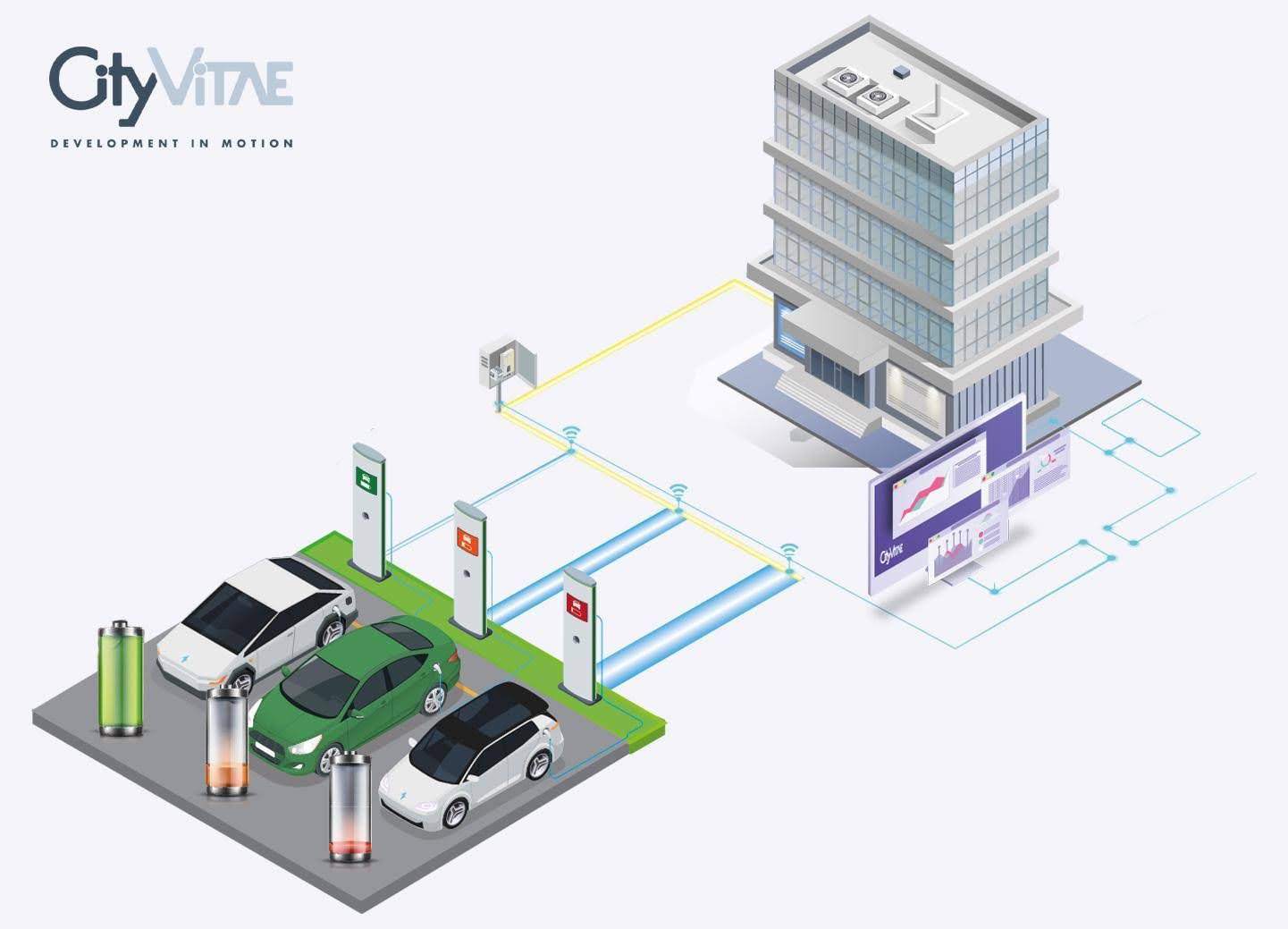

Remember that 80% of the total charge of an electric vehicle will be made in private space. Either at the office or home for long periods of several hours with very slow but economical chargers that will fill the battery in 6 to 8 charging hours. The remaining 20% will be done in public space. Although a minority percentage, this is key because these are situations where we do not have hours but rather minutes available. At the dentist, at the cinema or during our weekly shopping. 80% of the charging stations in the public space will be slow and will also require some hours to fill our tank/battery. 20% of the stations in public space will be fast and will recharge our battery in just over an hour.

The charging time factor is more important for an electric vehicle than for a conventional one. And the time of a car occupying a public space can be either very valuable (in Boston or NY the parking time can be as high as US$7/hour) or very economical (in any faraway small town).

Recently in California, per-minute charging has been banned. Operators are allowed to charge various fees: connection fee, waiting fee after full load, parking fee…

In France, on the other hand, no unit of measurement has been forced or prohibited. However, it has been decided to require the installation of a MID-standard energy meter on all DC chargers billing by kWh. This makes the product more expensive and hinders the operators’ business model. IONITY for instance has reacted to the new standard by switching to time-based pricing.

Regarding the question of which tariff system to use, we recommend following the dominant factor in costs. If for example, the time is 80% of the value of the complete charge operation versus the kWh cost, we should charge by the minute. Otherwise, we should bill per kWh. The charger management systems (an IT software also called backend system) can use both or even a mix between them, (a possible revenue formula applied by the backend system could be “the first hour per kWh, and from the second one, a base rate per minute, up to the third hour, doubling from the fourth hour onwards to avoid over occupation of valuable space”). Of course, we have to avoid confusing the user with multi-step formulas, but giving him clear and precise information is not at odds with the sophistication of the price models.

As for the interference or not of the State in the monetization models, similarly, as with the gas pumps, the taxi meters, or the parking meters, it would be good to have a sort of certification for electric vehicle chargers, both per kWh and per minute. But, having this certificate does not require the government to influence any brand or model or technical solution on a charger. If they did, they would interfere with market rules that are creating the necessary incentives to reach the deployment of millions of chargers that we will strongly need in the next months.

Anna Mª Francino, Business Developer, CityVitae